The What, Why, and How of Git and GitHub

Updated: January 26th, 2026

Git and GitHub are widely used tools in technical projects. Despite their prevalence, many rote memorize Git commands for straightforward tasks without fully understanding what these tools are, how they differ, and what roles they play in a project. In this section, I will provide an overview of Git and GitHub and explain why it is worthwhile to learn and use them over other available options.

What exactly are Git and GitHub?

Updated February 23rd, 2020. Accessed October 2025.

There are two types of version control systems that facilitate project sharing and collaboration: centralized and distributed 1. Git is a Distributed Version Control System (DVCS). In a DVCS, a remote server stores the central copy of a project, while complete mirrors containing the full change history are distributed to individual contributors who act as clients 2,3. Changes are synchronized in a peer-to-peer manner, with contributors committing modifications locally and then sharing them with others through patches transmitted via the server. The video clip on the left shows this process in action 4–6.

Downloaded October 10th, 2024.

Git was first released in 2005 and is the most popular version control system, surpassing both centralized and distributed alternatives 1,7,8. However, Git does not come with its own Graphical User Interface (GUI) and lacks infrastructure for project sharing and collaboration 9. Users must execute Git commands through a Command-Line Interface (CLI) like Terminal, which uses Bash—a Unix shell—presenting a steep learning curve for those unfamiliar with command-line environments 10,11.

GitHub was launched in 2007 to enhance Git’s functionality by providing a centralized, web-based platform for hosting and collaborating on repositories 11,12. It does not offer its own version control paradigm but rather builds upon Git’s framework, extending it with collaborative features such as the Fork and pull requests. The platform also enhances project management by providing tools that enable development teams to set milestones, assign responsibilities, and track issues 12.

Together, Git and GitHub enable robust code-based project management for individual and collaborative efforts. Both are language-agnostic, supporting any programming language, and work with IDEs either through native integration or as external tools 11.

OK, but why choose them over other options?

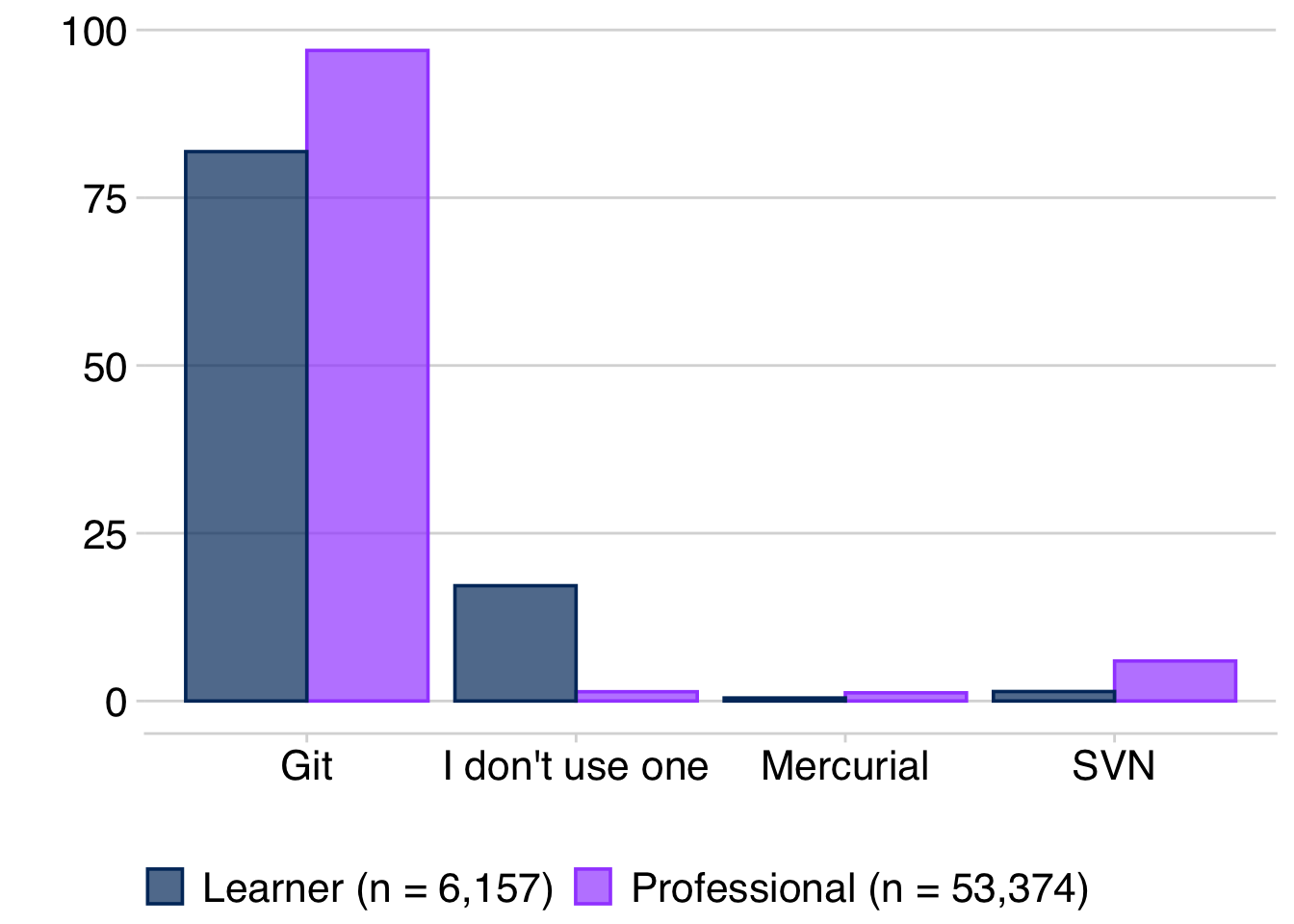

Git is by far the most popular version control system among both learners and professionals. According to a 2022 StackOverflow survey, more than 95% of professionals reported using Git in their work, compared to other systems such as Mercurial or SVN 8. Git is widely adopted by coding learners, though version control remains underutilized in this group. About 17% of learners use no version control, compared to just 1% of professionals.

2022 report.

GitHub is a leading platform for hosting free and open-source code, with over 100 million developers and more than 420 million repositories as of 2024 11,12. It surpassed its main competitor, SourceForge, in 2015 to become one of the world’s largest source code hosts 13.

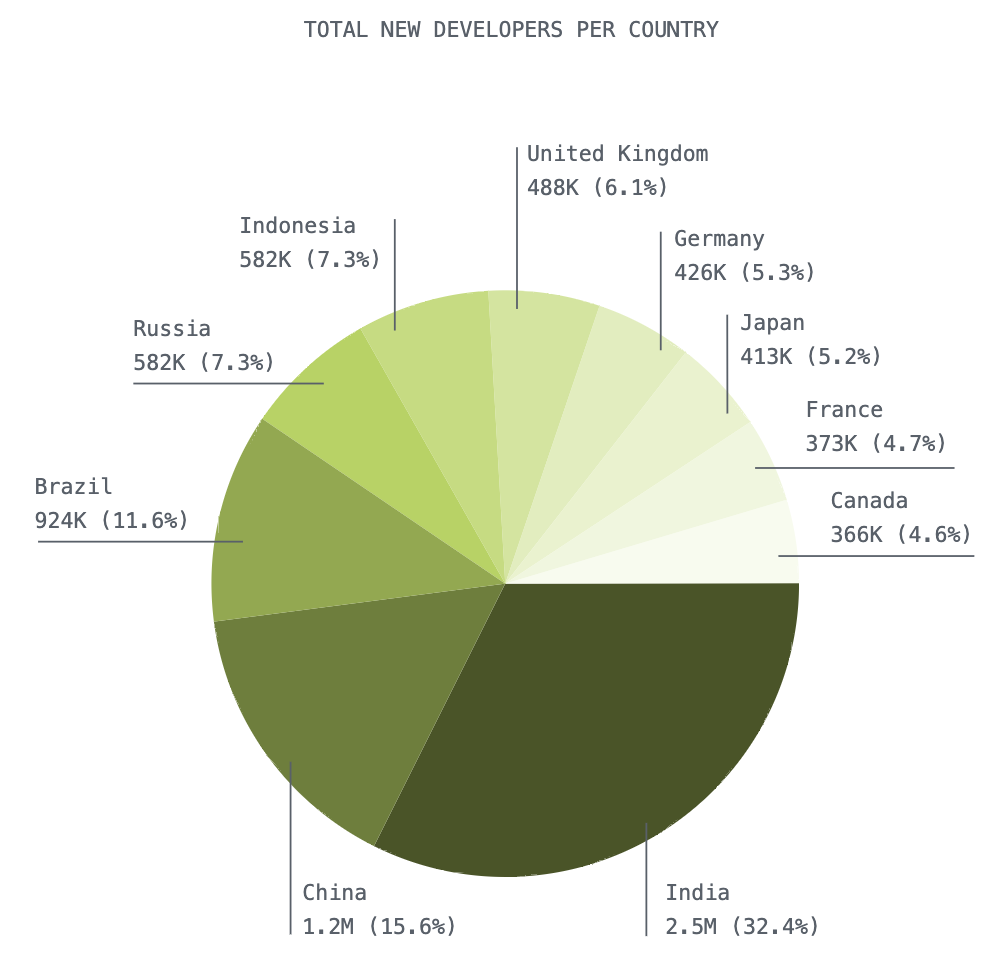

GitHub is a highly sought-after resource for maintainers and contributors worldwide, including developers working for companies and nonprofits. The pie chart on the right highlights 20 communities outside the U.S. with the largest user growth in 2022 compared to the previous year. In 2013, most users were based in the U.S., but with the year-over-year growth of users from India observed thus far it is expected that Indian programmers will match the U.S. developer population in 2025 14.

Essential Takeaways

With this introduction, we’re ready to start exploring how these tools handle version control and code distribution. While the contextual overview presented thus far is valuable for new or beginner users of Git and GitHub, let’s take a step back and review the core principles that you actually need to know before diving into the how.

The Motivations: In a coding project, it is often advantageous to track changes made at each step. When something goes wrong, version control allows you to easily diagnose which changes caused the bug and revert to older, working versions while you isolate and fix the issue. Think of it like “going back to the last save” in a game. Robustly managing a code-based project is only part of the challenge; you also need to provide means for accessing the work for publishing, reporting, or collaboration.

The Short and Sweet Descriptions: Git is a system that allows you to save, manage, and track code version histories, enabling you to revert to previously saved versions when necessary. GitHub builds on the Git framework, offering remote storage, distribution, and collaboration for Git-controlled projects 1,12. Some refer to GitHub as more than just a place to distribute code, but as a “social networking site for programmers” 11.

Unpacking How: Git and GitHub in Action

In the following chapter pages, we’ll guide you through installing Git, setting up a GitHub account, and configuring both. The rest of the chapter explores working with Git and GitHub through a realistic example and three common scenarios for managing project codebases, with opportunities to practice using pre-prepared problems.

Before diving in, I want to address a common complaint: many Git and GitHub introductions present commands out of context or as need-to-know information, making it hard to see the big picture. This approach makes grasping the basics challenging and often sends users down rabbit holes trying to piece together a cohesive understanding. It also complicates extending beyond basic usage, as it’s unclear how concepts apply to your own work.

To mitigate this confusion, the following section offers high-level key takeaways about how Git and GitHub interact with your project materials and with each other. We can divide this interaction into three main categories:

- Version Control on Your Device

- Remote Storage and Distribution

- Safeguarding Information Transfer Processes

This workshop focuses on core commands necessary for all projects rather than covering every method for moving files through version control domains. Additional commands exist that may better suit specific coding needs.

Version Control on Your Device

As explained above, Git handles version control, while GitHub builds upon Git to add collaboration and code sharing features. All necessary version control functionality for your projects therefore occurs locally on your device.

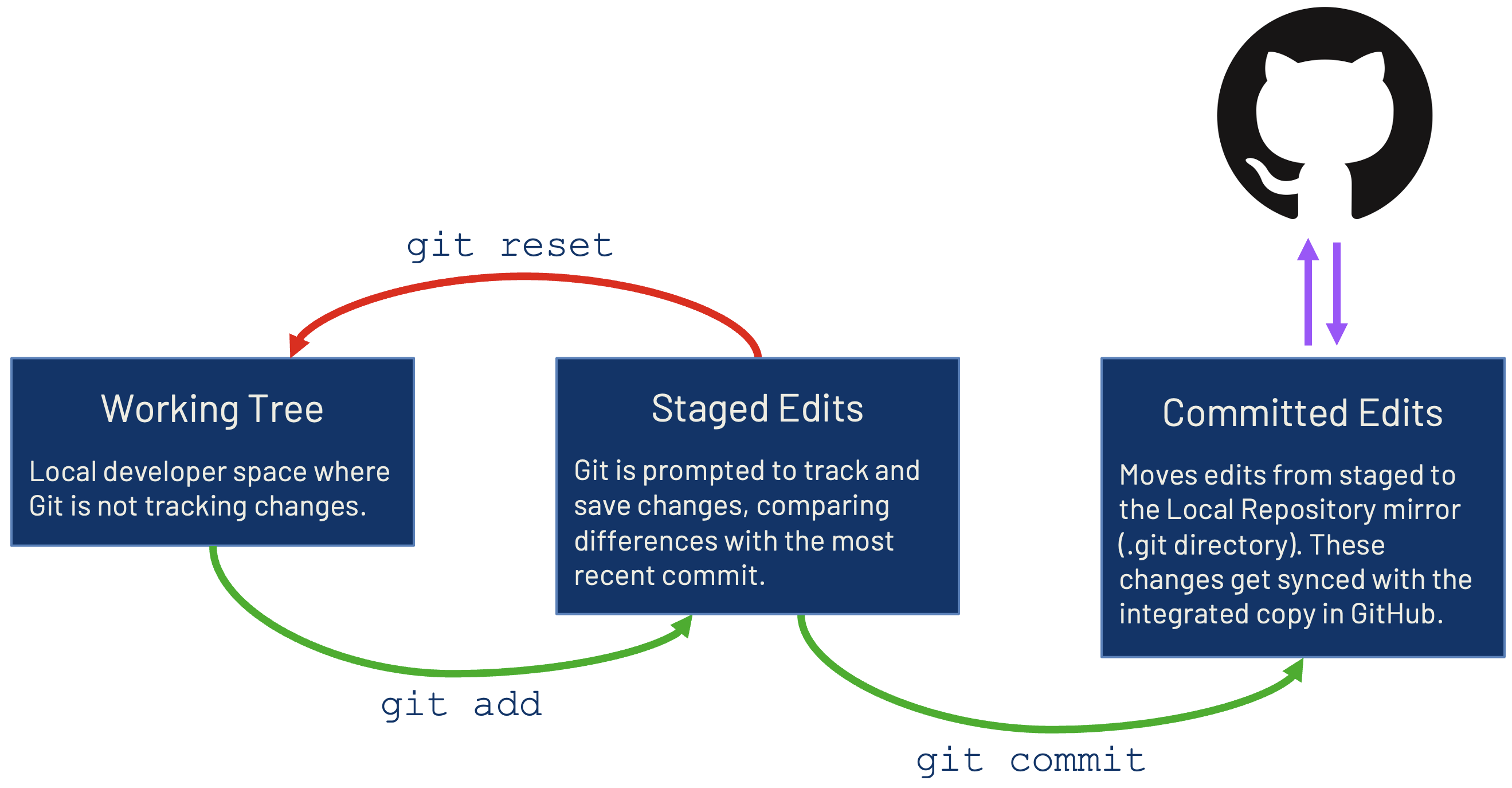

Projects are typically stored in a directory (a folder) containing all relevant files and code. A Git-initialized project will include a .git folder in the root directory, which contains all of the project’s version control history and status. Git interprets the project contents as existing in one of three domains at any given time: the Working Tree, Staged Edits, and Committed Edits 15. Note that some resources may use slightly different terminology for these domains, though most describe and categorize them similarly. These domains and common transitional commands are demonstrated in the figure below.

The Working Tree is the area where developers make changes to files in the project. In this domain, Git doesn’t actively track changes; instead, changes are recycled back into the same file without recording interim revisions. When you are ready for Git to follow changes, you need to add them to the staged environment with git add 16. This prompts Git to identify differences between Staged Edits and already committed versions that are stored in the .git directory. Files can be unstaged and restored to the Working Tree with the git restore command 17,18.

When tracking changes, Git uses a heuristic to compare files in your project directory and determine if a file has changed or is new. This change detection method is not always perfect and may sometimes mistakenly identify significantly altered files as new ones 19. Depending on the Git version, this may occur when renaming or moving a tracked file. Some versions interpret this as both creating a new file (with the new name or location) and deleting the old file 19,20. This can make reviewing the project’s version history confusing!

If you see this, it’s best practice to track a file rename or move action with the git mv command and to stage the modification for its own commit with an appropriate message 20,21.

Command-Line Application

# Track moving a file

git mv <source>/filename.txt <destination>/filename.txt

git add <destination>/filename.txt

git commit -m "Move filename.txt from <source> to <destination>."

# Track renaming a file

git mv oldfilename.txt newfilename.txt

git add newfilename.txt

git commit -m "Rename oldfilename.txt to newfilename.txt."Once you have reviewed the detected changes and approve saving them, use git commit to promote the staged version to the latest copy in the .git directory 16. The most recent Committed Edits are then available for syncing with the remote GitHub repository through a “peer-to-peer” patch. These core commands are used regardless of whether the file being tracked is new or has prior versions saved in the project .git directory.

Use git status to check the current state of your project files in the Working Tree and Staged Edits. Git will identify untracked files and prompt you to add them for version control. Remember, the local copy of the repository does not continuously monitor the remote repository. Instead, it maintains a copy of the remote repository’s contents from the last check 15.

Remote Storage and Distribution

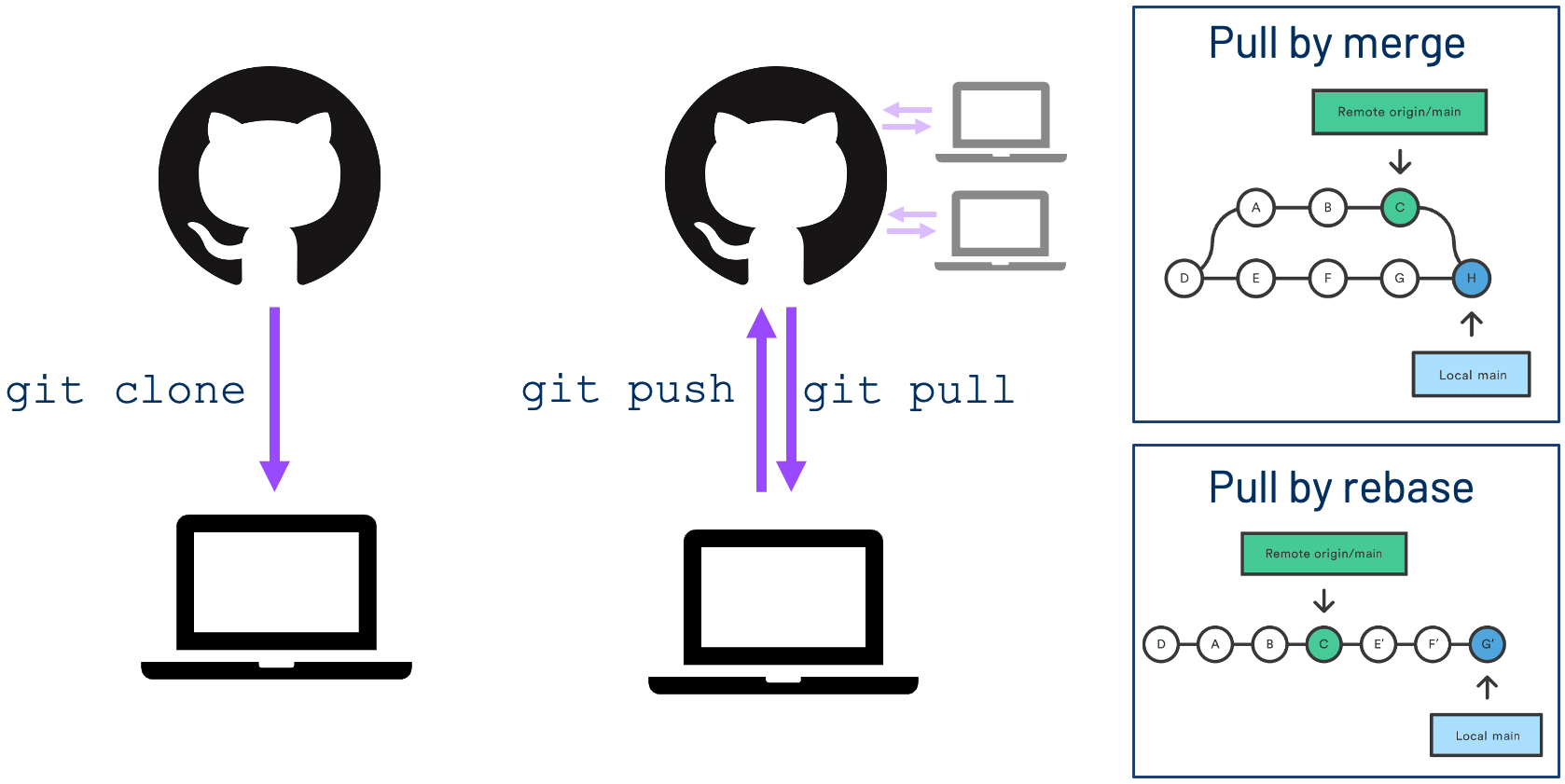

When using Git to interact with a remote repository on GitHub, there are three core commands: git clone, git push, and git pull. These operations will be covered in greater detail later in this chapter, so don’t worry too much about their exact differences right now. The figure below illustrates the subtle distinctions between these commands.

git merge and git rebase are from Atlassian’s “Getting Git Right” tutorial 22,23.

To create a local, mirrored copy of a remote repository on GitHub, use git clone. This one-time command downloads and stores a complete copy of a repository on your local device. Note that this does not automatically grant you permission to contribute changes directly to the repository; contributing requires the appropriate credentials 24. Some more on this in the next section!

git pull updates your local copy of the codebase to match the remote repository, a process known as “pulling” 25. Pulling is not the same as cloning; it’s used throughout the project’s lifetime to synchronize changes between your local and remote copies. A pull operation consists of two Git commands: git fetch and either git merge or git rebase.

git fetch brings a copy of the specified remote repository’s branch contents into a separate branch, allowing users to inspect the differences before integrating the two 26. git merge and git rebase are different approaches to reconciling divergent branches and should be chosen based on the coder’s skill level and whether the GitHub repository is used for collaboration or only for code distribution 22,23,25. These concepts will be covered in more depth later, but for now, refer to the right-most part of the above diagram for an indication of how they differ.

git push uploads your most recent committed edits from the .git directory to the remote GitHub repository, where they are evaluated for coalescence with the existing codebase 16. The most recently committed copy of the codebase is generally referred to as HEAD. Git uses HEAD in many aliases that refer to current versions—for example, FETCH_HEAD refers to the most recent copy of a remote repository branch that was fetched 27.

Safeguarding Information Transfer Processes

When your local device interacts with GitHub, several security checks are performed to protect your data 28:

- Verify that you’re communicating with the real GitHub, not an impostor site

- Confirm you have the necessary permissions to access specific content

- Encrypt data transfers to safeguard your content from potential intrusions

GitHub supports two authentication and communication protocols: Secure Shell (SSH) and Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) 29–32:

- SSH uses a pair of keys—a private key and a public key. Information is encrypted when sent between servers, and only the matching key pair can decrypt it upon receipt.

- HTTPS facilitates secure transmission of information over an encrypted internet connection. Decryption occurs when the correct username and Personal Access Token (PAT) are provided.

The transfer protocol is defined when first establishing a connection between your local and remote repositories. This is done by specifying the remote repository’s URL in the local project’s Git configuration and assigning it an alias, usually origin. Below are examples of what SSH and HTTPS URLs would look like for repository “ORIGINAL-REPOSITORY” and user ysph-dsde on GitHub.

Command-Line Application

# SSH

git@github.com:ysph-dsde/ORIGINAL-REPOSITORY.git

# HTTPS

https://github.com/ysph-dsde/ORIGINAL-REPOSITORY.gitYou can set different protocols for different project directories and change the protocol associated with a given project later 33,34. Additionally, you can define multiple remote repositories for the same project directory, such as copies of the repository in GitHub, GitLab, or other platforms 27. See the citations for details.

This may be familiar if you’ve already created or cloned repositories in GitHub, but don’t worry if not—the Worked-Through Example and hands-on portion of this workshop will show you exactly where to find and use this URL. For a complete breakdown of SSH and HTTPS with a pros-and-cons table and step-by-step configuration instructions, see Transfer Protocols on the Configurations and Credentials page.

Moving Ahead

With this overview, you have the foundational understanding of Git and GitHub necessary to effectively proceed with the remainder of the workshop. As you go through the remaining pages, we recommend returning to this overview from time to time to better connect the concepts presented here with their application.

Section Glossary

| Command-Line Interface (CLI) | A texted-base application that directly interacts with the computer’s operating system, manages files, and can run programs. It typically lacks a GUI 10. |

| Distributive Version Control System (DVCS) | The project codebase is copied as a mirror to each contributor’s local computer. Local changes get synched via patches sent "peer-to-peer" through the server 1,4. |

git add

|

Prompt Git to track changes made to specified files and transition them from the Working Tree to the Staged Edits domain. Git compares the added files to any previously saved versions available in the .git directory 16.

|

git clone

|

Copies an existing repository stored in a remote server to your own device, including all files, the version history, and branches 24. |

git commit

|

Promote the staged version of specified files to become the latest copy reflected in the .git directory. The Committed Edits version is what gets synced to the remote server as a “peer-to-peer” patch 16.

|

git fetch

|

Downloads the remote branch contents into a separate local branch for review before integration. Part of the pull action 26.

|

git merge

|

One method to reconcile different committing histories in divergent branches. Creates a new version integrating the head of the two branches in a three-way commit 22,25. |

git mv

|

Moves or renames a specified file, directory, or symlink that is already tracked by Git 21. |

git pull

|

Downloads a copy of the specified remote repository’s branch and integrates it with the local copy. Combines the actions of git fetch followed by git merge or git rebase 25.

|

git push

|

Upload your recent Committed Edits to a remote repository, synchronizing changes for others to see 16. |

git rebase

|

An alternative to merge. The branch commit histories are realigned so that the leading one defines the commit parent history of the following branch, thus rebasing its commits 23,25.

|

git restore

|

Reverts content in the Working Tree or Staged Edits to their last committed state. Adding the –staged option will move files from Staged Edits back to the Working Tree, without overwriting any new changes there 17,18.

|

git status

|

Summarizes the state of files in the Working Tree and Staged Edits, comparing changes to the latest, committed version in the .git directory.

|

| Graphical User Interface (GUI) | An interface that allows users to interact with computers through visual elements like buttons and menus 9. |

| HTTPS (Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure) | Facilitates secure transmission of information over an encrypted internet connection. Decryption occurs when the correct username and Personal Access Token (PAT) are provided 28–31. |

| Mirror | An exact copy of a project from a server, including al files, the version history, and branches 3. |

| Patch | Snippets of code or data used to update existing software 6. |

| Peer-to-peer | Participants in a network act as both client and server by trading resources and services with one another 5. |

| Root directory | The top-most directory in a branched hierarchy, containing all other files and directories. Your project’s root directory holds all the relevant files and code used your project. |

| Server and Client | Servers are computers or systems that provides resources (i.e. data or programs) to other computers, known as clients, over a network 2. |

| Shell | A program used by the CLI to mediate communication between the user and computer by interpreting commands and outputs. Examples: Bash, PowerShell, etc 10. |

| SSH (Secure Shell) | Uses a pair of keys—a private key and a public key. Information is encrypted when sent between servers, and only the matching key pair can decrypt it upon receipt 28,30–32. |

| Version Control | Manage, organize, and track different versions of files. Identify differences between versions and allows reverting to older versions 1. |